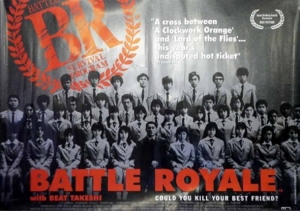

Batoru Rowaiaru

2000/Japan

Directed by Kinji Fukusaku

Screenplay by Kenta Fukusaku based on novel by Koushun Takami

Stars: Takeshi Kitano, Aki Maeda, Tatsuya Fujiwara, Chiaki Kuriyama, Taro Yamamoto, Sousuke Takaoka, Takashi Tsukamoto, Yukihiro Kotani, Eri Ishikawa, Sayaka Kamiya, Aki Inoue, Takayo Mimura, Kou Shibasaki, Masanobu Ando, Ai Maeda, Minami

Production Co: Toei Company Ltd.

Music by Masamichi Amano

Thriller, gore, j-horror

El sábado pasado vi por fin la primera entrega de la saga Los juegos del hambre y, sin desmerecer y que conste que no he leído el libro, me quedó una sensación tan “de que me sentía incompleta” que necesité urgentemente correr a mi colección de DVDs y ver Battle Royale. Y de ahí, de la necesidad de explicar la diferencia entre una obra maestra y una idea a medio hacer, surgió este post. (*≧∀≦*)

Last Saturday finally I was the first delivery of the series The Hunger Games and, no offense and stating that I have not read the book, I was feeling so “uneasy and incomplete” that I urgently needed to run to my DVDs collection and watch Battle Royale. And hence, the need to explain the difference between a masterpiece and a half-thought, appeared this post. (*≧∀≦*)

Hablar de Kinji Fukusaku es como hablar del yakuza eiga en sí mismo. Nacido en 1930 en Mito, el director fue uno de los primeros en introducir el realismo en el género, hasta tal punto que a sus películas se las considera jitsuroku eiga (documentales reales). Y es que el yakuza eiga hasta los 70 (conocido como ninkyo eiga o películas de caballeros) había pecado en exceso de romanticismo describiendo a los protagonistas yakuza como hombres honorables que se movían en los límites entre el deber y el sentimiento. Pero Fukusaku supo romper perfectamente con esta visión en su filmografía con cintas como Boss (1969) o Wolves, Pigs and People (1964) aunque una de sus películas más aclamadas del género es sin duda Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1973), la adaptación de los artículos periodísticos de un ex-yakuza sobre la guerra entre bandas en Hiroshima después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Podríamos decir que el realismo de sus películas se basa en parte en la introducción de la violencia; cuando el yakuza del ninkyo eiga traspasa la línea del deber y se olvida del sentimiento, y la violencia hace que el espectador lo entienda como el antihéroe. Es precisamente esa visión crítica lo que le lleva a dirigir Battle Royale donde la violencia es toda una institución. Es cierto que no toda su filmografía se basa en yakuza eiga, pero la aportación que hizo al género y el tratamiento particular de la violencia son innegables. Fukusaku es sin duda uno de los directores japoneses más prolíficos con algo más de 60 películas y 23 guiones; un trabajador inagotable que cedía ante el cáncer en enero de 2003 mientras dirigía la secuela de Battle Royale después de rodar una escena con Kitano, en la saga que dejaría su crítica más mordaz a la violencia.

Speaking about Kinji Fukusaku is like speaking of yakuza eiga itself. Born in 1930 in Mito, the director was one of the first to introduce realism in the genre, so much so that their films are considered jitsuroku eiga (real documentaries). And is that the yakuza eiga until 70s (known as ninkyo eiga o chivalry films) had sin in excess of romanticism having portrayed yakuza main characters as honorable men moving in the boundaries between duty and feeling. But Fukusaku knew how to break perfectly with this vision in his films like Boss (1969) or Wolves, Pigs and People (1964) although one of its most acclaimed films of the genre is definitely Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1973), adaptation of the newspapers articles of a former yakuza about gangs walfare in Hiroshima after WWII. We could say that the realism of his films are based in part on the introduction of violence, when the ninkyo eiga crosses the line of duty and forget the feeling, and violence makes the viewer understands him as the antihero. It is precisely this critical vision which leads him to direct Battle Royale in which violence is an institution. It is true that not all his movies are based on yakuza eiga, but the contribution he made to the genre and the particular treatment of violence are undeniable. Fukusaku is undoubtedly one of the most prolific Japanese directors with more than 60 films and 23 screenplays, a tireless worker who yielded to cancer in January 2003 while directing the sequel to Battle Royale after shooting a scene with Kitano in the saga that would become his most scathing criticism for violence.

El film está basado en la novela homónima del escritor Koushun Takami (バトル·ロワイアル) en la que el Japón de 1997 es una región miembro de un estado autoritario llamado Gran República del Asia Oriental. Bajo la excusa de un viaje de estudios el déspota profesor Kitano enrola a sus alumnos en el programa Battle Royale como resultado de la Ley Battle Royale, un proyecto de investigación militar ideado para aterrorizar a la población y hacer de la insurrección un imposible. A partir de ese momento los 42 alumnos de la clase 3B de Kitano serán confinados en la isla ficticia de Shodoshima (a semejanza de la isla del Mar Interior de Seto Ogijima) para matarse entre ellos ateniéndose a sólo cuatro reglas: 1) el programa dura tres días; 2) cada jugador tiene un kit de supervivencia con agua, comida y un arma; 3) si sobrevive más de un jugador, se detonarán los collares electrónicos que llevan y todos morirán; 4) no hay forma de escapar.

The film is based on the homonymous novel of the writer Koushun Takami (バトル·ロワイアル) in 1997 in which Japan is a member country of an authoritarian state called Greater Republic of East Asia. Under the guise of a study tour, a despotic professor Kitano enrolls his students in the Battle Royale Program result of the Battle Royale Act, a military research project designed to terrorize the population and make the insurgency impossible. From that moment the 42 students in the class 3B of Kitano will be confined to the fictional island of Shodoshima (similar to the island of Ogijima in Seto Inland Sea) to kill each other in compliance with only four rules: 1) the program lasts three days; 2) each player has a survival kit with water, food and a weapon; 3) if more than one player survives, the electronic collars will be detonated and they will all die; 4) there is no way to escape.

El filme describe una situación antiutopía producto del fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. En esta nueva sociedad capitalista en extremo la cooperación carece de importancia y se aboga, en cambio, por la competitividad de las cualidades individuales. Se podría decir que la historia se basa en como responde cada personaje ante esta situación. Pero hay mucho más que violencia en esta cinta. Primero el “Requiem” de Verdi (interpretado por la orquesta filarmónica de Varsovia dirigida por el compositor japonés Masamichi Amano, a cargo de la banda sonora de la película) que nos muestra la situación de desesperación en la que está sumida la sociedad: 15 % de desempleo y 800,000 alumnos boicoteando las escuelas hicieron que los adultos perdieran la fe en la juventud y aprobaran la Ley Battle Royal. Y segundo, la imagen de la niña que ha ganado el último programa, llena de sangre, completamente ida y ofreciendo una imagen sádica y terrorífica. No es casual, pues, que el padre de Shuya (Tatsuya Fujiwara) se suicide al no conseguir un empleo y le anime sin embargo en su última nota: “Vamos Shuya. Tú puedes hacerlo, Shuya.” El mundo adulto no puede dar una respuesta correcta a la situación actual y lo deja en manos de las nuevas generaciones. Además, el hecho de que la clase escogida sea de 9º grado no es casualidad sino una crítica velada al sistema educativo japonés, ya que en el 9º grado los alumnos japoneses se enfrentan a los exámenes estatales en los que compiten en nota para poder acceder a las mejores Escuelas de Bachillerato. El estado de estrés en este año es tal que hay alumnos que se hunden y caen en el suicidio.

The film describes a dystopia situation result of the end of World War II. This new extremely capitalist society where cooperation is unimportant the response is the competitiveness of individual qualities. You could say that the story is based on how each character responds to the situation. But there is much more violence in this film. First, Verdi’s “Requiem” (played by the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra directed by the Japanese composer Masamichi Amano, in charge of the soundtrack of the movie) that shows the desperate situation in which society is sunk: 15% unemployment and 800,000 students boycotted schools made that adults lose faith in youth and pass the Battle Royal Act. And second, the image of the girl who has won the last program, full of blood, completely mad offering a sadistic and terrifying image. It is no coincidence, then, that the father of Shuya (Tatsuya Fujiwara) commits suicide because he fails in getting a job but cheers up Shuya in his last note: “Go on Shuya. You can do it, Shuya“. The adult world can not give a correct answer to the current situation and leaves it in the hands of the younger generation. Furthermore, the fact that the chosen class is in 9th grade is no accident but a veiled criticism to Japanese students face state exams an compete in note to access the best high schools. The status of stress in this year is such that there are students who collapse and commit suicide.

Fukusaku reconoció que la violencia extrema que utiliza en esta película proviene de cuando él trabajaba durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial en una fábrica de munición. A sus 15 años veía a menudo como sus amigos volaban literalmente por los aires e incluso tenía que recoger sus miembros después de los bombardeos de los aliados. Sin embargo, y a pesar de la desilusión que representa el profesor Kitano, el filme acaba con la esperanza puesta en el futuro de la nueva generación. Volvemos a ver entonces la misma conclusión que en Perro Rabioso: la esperanza puesta en la generación que hará resurgir al nuevo Japón de sus cenizas.

Fukusaku recognized that using extreme violence in this film comes from when he worked during World War II in a munitions factory. In his 15 years he often saw his friends literally blow up an even had to gather their members after the allied bombing. However, despite the disappointment that represents the teacher Kitano, the film ends with hope in the future of the new generation. We again see then the same conclusion as in Stray Dog: hope in the generation that will emerge Japan from the ashes again.

Pero como decía, lo más interesante del filme es como responde cada alumno ante esa situación de desesperación. Por ejemplo, el chico número 19 Shinji Mimura, sobrino de un activista de los 60 (Takashi Tsukamoto quien en Outrage volvemos a ver junto a Kitano) actuará con una filosofía colectiva; O la chica número 11 Mitsuko Souma (interpretada por Kou Shibasaki de Memorias de Matsuko), que proviene de una familia desestructurada en la que han abusado de ella sexualmente y resuelve tomar venganza en la isla de una manera completamente sociopata; O el chico número 6 Kazuo Kiriyama (Ando Masanobu) utilizado por los militares para reducir las posibilidades de cooperación entre los jugadores y que mata sólo para poder ir a una escuela mejor.

But as I said, the most interesting part of the film is how each student responds to this situation of despair. For example, boy no. 19 Shinji Mimura, nephew of an activist of the 60s (Takashi Tsukamoto whom we’ll see again in Outrage together with Kitano) will act with a collective philosophy; Or the girl no. 11 Mitsuko Souma (played by Kou Shibasaki of Memories of Matsuko), who comes from a dysfunctional family in which she’s been sexually abused and resolves to take revenge on the island in a completely sociopathic way; Or boy no. 6 Kazuo Kiriyama (Ando Masanobu) used by the military to reduce the chances of cooperation between players and killing just to go to a better school.

Battle Royale se llevó cuatro galardones en la 24 edición (2001) de la Japan Academy Price: Logro Sobresaliente en Montaje para Hirohide Abe, Novato del Año para Tatsuya Fujiwara (Light Yagami en Death Note), Novata del año para Aki Maeda y el de Película Más Popular. En los Blue Ribbon Awards (2000) se llevó el de Mejor Película y Novato del Año. Pero sin duda su reconocimiento ha ido mucho más allá de los premios recibidos. Battle Royale está considerada toda una película de culto entre los amantes del género siendo la primera que introduce un juego de muerte entre adolescentes e influyendo a directores occidentales tan reconocidos como Quentin Tarantino –quien la reconoce como su película favorita–. De hecho el personaje de la chica número 13 Takako Chigusa (interpretado por la actriz y cantante Chiaki Kuriyama) es exactamente el mismo personaje que aparece en Kill Bill como Gogo Yubari: un producto de la violencia.

Battle Royale took home four awards at the 24th edition (2001) of the Japan Academy Price: Outstanding Achievement in Film Editing for Hirohide Abe, Rookie of the Year for Tatsuya Fujiwara (Light Yagami in Death Note), Rookie of the Year for Aki Maeda and the Most Popular Movie. In the Blue Ribbon Awards (2000) won the Best Picture and Rookie of the Year. But undoubtedly its recognition has gone far beyond the awards received. Battle Royale is considered and entire cult movie among the fans of the genre being the first to introduce a game death among teenagers and influencing Western renowned directors such as Quentin Tarantino –who recognizes it as his favorite movie–. In fact the character of the girl number 13 Takako Chigusa (played by actress and singer Chiaki Kuriyama) is exactly the same character featured in Kill Bill as Gogo Yubari: a product of violence.

Creo que no necesito dar razones para explicar por qué Battle Royale se ha convertido en un clásico de culto pero quiero hacerlo: 1) es una película completa, aunque tenga una secuela el hilo argumental no se deja cabos sueltos y podría funcionar perfectamente sin segundas partes; 2) es un experimento sociológico en sí mismo, no se trata de ensalzar un héroe o una conducta adecuada, sino de entender las diferentes respuestas ante una situación determinada; 3) la banda sonora es perfecta; 4) el montaje es excelente; 5) las escenas de violencia aunque justificadas son de una realidad apabullante. El mejor j-horror en estado puro.

I think I don’t need to give any reasons to explain why Battle Royale has become a cult classic but I wan to: 1) it’s a complete movie, even though it has a sequel the plot is not left loose ends and could work perfectly well without second parts; 2) it’s a sociological experiment in itself, it is not about praising a hero or an appropriate behaviour, but to understand the different responses to a given situation; 3) the soundtrack is perfect; 4) the assembly is excellent; 5) scenes of violence are justified although an overwhelming reality. The best j-horror at its best.

Fuentes:

Desjardins, Chris. Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. New York: I.B. Tauris, 2005.

McRoy, Jay. Japanese Horror Cinema. Edinburg: Edinburgh University Press, 2005.